Shadows of the Emerald City Review by Greer Woodward October 15, 2009 – Posted in: Book Reviews, Reviews

Darkness Gathers, Yet Oz Remains Undaunted

Darkness Gathers, Yet Oz Remains Undaunted

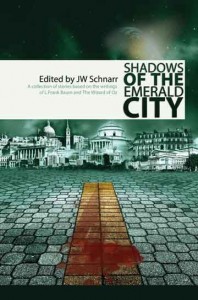

Shadows of the Emerald City

Edited by JW Schnarr

Published by Northern Frights

Reviewed by Greer Woodward

When I originally read L. Frank Baum’s Oz books, two things struck me about the magical kingdom, its breadth – that there were always new characters, communities, and challenges around the bend – and that I very much wanted to go there. Now I’m far away from those bountiful days of childhood, but I’m pleased to report that Shadows of the Emerald City, JW Schnarr’s 19-story anthology about the dark side of Oz, offers a sense of Oz’s continuing expansiveness as well as a satisfying number of characters that yearn to be part of the enchanted land.

The anthology is a mix of stories featuring well-known characters from The Wizard of Oz – Dorothy, Scarecrow, Tin Man, Wizard, and Witches; lesser-known personalities from the later series – Jack Pumpkinhead, Mr. Yoop, the China People, and Fuddles; several new relations – Dorothy’s father, Dorothy’s husband, and the Scarecrow’s son; and new creations altogether – good-looking gumshoe Captain Jo Guard, botanical specialist Linnaea, and the heroic warrior Trewis and his decaying nemesis Ozymandias.

The range of characters combined with a variety of approaches and themes does well to suggest Oz’s unlimited landscape. Alternate mythologies, noir takes, origin stories, second chances, and absurdist directions smoothly and effectively link with traditional horror themes – greed, murder, the quest for power, and cannibalism, especially in witches with a taste for children.

One of the most successful alternate mythology pieces, “The Utility of Love” by David Steffen, chronicles the relationship between Dorothy and Tin Man, in this incarnation a heartless assassin. Tin Man wants Dorothy to teach him about love, a request which juxtaposes Dorothy’s simple thoughts about affection for friends and parents with complex moral situations: lying, killing, the intentional death of a beloved companion, and a deal with the dark side. The qualities of love spin and sputter, shifting from meaning to nothingness to meaning again as events swiftly change.

For noir takes, Shadows offers an entertaining trio. Jack Bates’ “Emerald City Confidential” features a reluctant sleuth, double-dealing over-the-top sirens, and a hidden power struggle of monumental proportions. “Four AM at the Emerald City Windsor” by H.F. Gibbard examines a marriage gone bad, in this case, the union of Dorothy Gale and Bert Lister, formerly The Great Cagliostro, master of might and magic, now a hopeless and possibly murderous drunk.

Lori T. Strongin’s “Not in Kansas Anymore” is also about an older Dorothy, this one a stripper who calls herself “Kansas.” In the opening paragraphs she regrets her youthful expectations, not knowing then that Oz was “the place where innocence went to die; where broken hearts met broken glass, and blood was just graffiti on emerald green walls.” The narrative takes her through a garish replay of the events of The Wizard of Oz, with monstrous embodiments of her former friends, leading her to question the truth of what she is experiencing and the source of the horror.

But several of the stories I found most memorable looked at the disturbing implications of some of Oz’s quaint, distinct, and originally delightful notions, most in books following The Wizard. Rajan Khanna’s skillful “Pumpkinhead” and Jason Rubis’ darkly amusing “A Chopper’s Tale” involve the magic Powder of Life, known for animating Jack Pumpkinhead, the Sawhorse, and the Gump in Baum’s 1904 The Marvelous Land of Oz. In “Pumpkinhead” the powder goes terribly wrong and in “A Chopper’s Tale” it goes terribly right, at least from the point of view of the narrator, a psychopathic axe.

“Mr. Yoop’s Soup” and “The Fuddles of Oz” consider the downside of one of the most famous benefits of living in Oz: its citizens do not die. Michael D. Turner’s soup story is very funny, but may not be for the queasy. Mr. Yoop, a giant cannibal first appearing safely behind bars in 1913’s The Patchwork Girl of Oz, has escaped and appropriated an antique, two-handed cleaver. Several subsequent scenes take place in the boiling meal between the disembodied – and chatty – heads of the King of the Munchkins, a goose girl, and a famous wrestler.

Baum devotes a chapter in his 1910 The Emerald City of Oz to the Fuddles, described as the most peculiar people in the Land of Oz. Each Fuddle is a living puzzle made of wooden pieces. Unfortunately when a visitor approaches, the pieces scatter and the Fuddles need the outsider to put them back together again. In the Baum book, Dorothy and her friends spend several amusing hours reassembling the Fuddles, but in Mari Ness’ story, a not very bright Winkie is befuddled by the Fuddles with unhappy consequences. It’s a beautifully structured little tragedy: the Fuddles are undone by their uniqueness and also by their obscurity – they are mere dots on the giant, continuously unfolding canvas of Oz.

And then there are the touching stories about finding a way into Oz – for the first time, or to return. T.L. Barrett’s “The China People of Oz” centers on Ronie, an eight-year-old fan of the Oz books who is dying of leukemia. On a trip to Kansas from the Grant-A-Wish Foundation, she finds a set of figurines in a memorabilia shop and is convinced they are the actual China People from one of the final chapters of The Wizard. Is Ronie a victim of her imagination or has she stumbled on something impossible, but nonetheless real? The story tenderly and perceptively explores this delicate question. Ronie’s feelings and actions ring true, as do those of her parents.

The first and last stories in the collection, Mark Onspaugh’s “Dr. Will Price and the Curious Case of Dorothy Gale” and Martin Rose’s “The King of Oz,” also consider the logistics of getting to Oz. The first examines what is necessary for a successful return, and both suggest that the most profound horror of all is losing – forever – one’s only golden chance.

In contrast to the stories about reaching Oz, editor Schnarr’s superb “Dorothy of Kansas” begins with Tin Man and Scarecrow leaving the magical country, not because they are dissatisfied or have grander plans, but because they want to save their home. Joy – and life – have left the land. The Emerald City is strewn with corpses; the sky is smoky, and acid snow falls constantly.

It’s a stark, absurdist journey, reminiscent of Samuel Beckett’s classic Waiting for Godot. Tin Man is covered with rust and crumbling, and nothing is left of Scarecrow but a stuffed head in a bucket. They seek Kansas and Dorothy in the hope she can restore the kingdom. What they discover is a bleak relationship between real and imaginary worlds. Just as Baum’s Oz reflected the optimism and possibility of the early 1900’s, Schnarr’s work captures the unsettled, angst-ridden spirit of ours: maybe the apocalypse won’t happen this week, but it’s out there, lurking.

If you’ve read the Oz books, you’ll enjoy what this anthology adds to the canon. If you’ve only seen the 1939 movie, there are enough red shoes, pink Glindas, and fragments of iconic dialogue to keep you interested. In fact, my only criticism of the anthology is that so many images come from the film, not the books. But perhaps that’s a sign of the times. If you google “The Wizard of Oz,” the first listings will likely reference the film. You’ll have to try “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” Baum’s original title, to find the book at the top of the heap.

Not that I mind, at least for long. I’ve ordered the 70th Anniversary version of the film and by the time you are engrossed in the expansive landscape of this shadowy anthology, I will be singing along with Dorothy. And both of us many wonder – even you on Schnarr’s considerably rockier pathway – if childhood wishes are so wrong, if it just might be possible somehow, someday to reach the Land of Oz.

1 Comment

Nat February 12, 2012 - 19:41

Sadly, Lori T. Strongin turned out to be a plagiarist most foul.